Charissa did a good job in the last entry describing the allure of the CREC and other patriocentric/familycentric churches. To most eyes–especially the conservative evangelical sort–they really do look like they’re doing things right with their families, and for parents concerned that their children are trained up in the way they should go, that seems very important. It also seems to be the logical extension of minds concerned with orthodoxy¹: if you’ve got the right doctrine, you’ll do other things right, too. That was one of the things that attracted me more than anything else, the emphasis on seeking the truth about everything (by means of analysis and argument). I was tired of sitting on the fence about things, tired of Christian relativism, tired of Christianized messages of secularism, tired of people saying it doesn’t matter what you believe as long as you love Jesus. Here in the CREC, it certainly did matter. It seemed clear: you could see it in the way they raised their families, the way they worshiped, the way they lived.

The problem is that, like Charissa said, things are not always as they appear to be. Some things are beautiful on the outside, but inwardly are full of dead men’s bones, as was true of the Pharisees (Matt. 23:27), and, I discovered, is also true of many families and churches in groups like the CREC.

The prevailing view of women in our parish was a low one. It was something I was never able to personally accept, but I endured it for years because I viewed it as nothing more than an annoying quirk, hardly worth parting ways over in light of the many positive features. And the fact is, on the surface it doesn’t even seem like women are oppressed there in any way. They don’t wear burqas, they can drive, no one is beaten or called names; they seem happy, even that they are embracing this life by their own free choice.

Spiritual abuse is insidious. It’s subtle, like its father the Devil, who comes to us disguised as an angel of light (II Cor. 11:14). The happy families, the high standards of morality, the ostensibly serious approach to theology…these things conceal and distract from the reality of spiritual misogyny that threatens the souls of women in these places.

But if you watch carefully, you can see it come out. Let’s take a look at just some of the ways in which this misogyny manifested itself in the parish to which I belonged:

1. “The sermon is for the men.”

Yes, the pastor actually said this, on more than one occasion. And no, he wasn’t talking about that particular sermon, but about every sermon. Sermons are for men. The men should listen, and then interpret it for their wives and children. The wives and children can be in the room while the sermon is being preached, but it’s not intended for them, because men are superior to women.

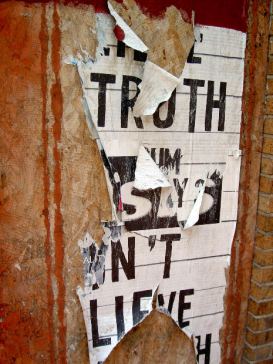

I thought about being fair and saying that it’s because wives are supposed to submit to their own husbands, but though it would seem nicer, it’s actually not true–because it’s not just about the differing roles of husbands and wives, but flat out men versus women, no matter how hard they try to convince us otherwise. Read on and you’ll see that I speak the truth.

2. Communion must be served to women by men

For the first several years, the pastor would call the men to the front of the church when it was time for Communion, and the men would take bread and wine back to their families and assist them in drinking from their family’s common cup. Later they modified it slightly so that the elders and deacons would carry the elements to the families, but it was basically the same thing because it was only to a male that it could be delivered to, except in extreme circumstances in which there was no male in the family.

For the first several years, the pastor would call the men to the front of the church when it was time for Communion, and the men would take bread and wine back to their families and assist them in drinking from their family’s common cup. Later they modified it slightly so that the elders and deacons would carry the elements to the families, but it was basically the same thing because it was only to a male that it could be delivered to, except in extreme circumstances in which there was no male in the family.

This wasn’t just a matter of preference. A woman was not to come to the front of the church and bring the bread and wine back to her family, even if her husband was away for some reason. Was she divorced or widowed? Was he out of town on business? Then send her son up–even if her son is a preschooler! This is not hyperbole; a four-year-old could come for the cup and bread and bring it up to his mother, who had to sit in her pew. Why? It wasn’t because he was cute, it was because he had the requisite genitalia.

I can’t tell you how sick this made me. I tried to ignore it but eventually it was infuriating, to the point that I didn’t even want to be in the room when we took Communion. I didn’t actually leave, because I felt it was important to partake, but I felt irritated and frustrated the entire time.

Once, after they had started having the elders bring the bread and wine to the “heads of household” (i.e., males), it so happened that I was sitting at the end of the pew nearest the elder, and it would have been an uncomfortable stretch for him to have to give it to my husband–so I did what any reasonable person would do and reached to take it from the elder myself. I was planning to then hand it to my husband. But no. The elder pulled it away from me and laughed at me, then pushed past me to give it to my husband, as is meet and right.

3. Women may not listen to church meetings.

Every so often, there would be a “men’s meeting” at church. Males of any age or position were welcome, but women were forbidden. In these meetings, church business would be discussed, including issues pertaining to the constitution, as well as theological questions and conversations.

As a thinking person, I was very interested whenever this sort of thing came up, so naturally I was very eager to hear what might be said in these meetings. I asked if I could listen in on them. I specifically said I had no interest in participating, but only hearing. But the answer was no. And just as in the above example about Communion, the elders laughed at me and began to refer to me as “Yentl“. It was all very patronizing, but I laughed along with him in order to prevent myself from exploding with resentment.

The same applied when I requested to join the men’s email list, which was the only list where there was doctrinal debate. The ladies’ list was all about diapers and homeschooling–all well and good, except that I really wanted to read the theological discussions, too.

But I was just a silly little girl, apparently. They smiled at and mocked me, and I wished I were a man.

4. A woman should not confront a man in any way.

Once I had a problem with something the pastor said in a sermon. I felt that he had inappropriately called out specific individuals on an issue that he didn’t actually understand and that was completely irrelevant. It’s a long story and I’m loathe to rehash it, because it was extremely petty and involved, but I was not the only one who felt that way.

I emailed the pastor and other elders and told them of my concerns. I wasn’t at all hostile or accusatory; I just wanted them to know that I was somewhat upset and that I felt the pastor didn’t understand the issue, so I wanted to give him my point of view.

I received a brief reply, and then my husband got a longer one, in which he was accused of “sending his woman to war”. After that, the entire discussion–which lagged on for a very long time–was between the men only, even though I was the one who had felt strongly enough about the actual issue at hand to take the time to ask them about it. (Another woman actually did this, too, and ended up in the same situation.)

This happened in other cases, too. One time the pastor actually criticized my father for the fact that I had “inserted myself” into a situation that was allegedly none of my business, even though I was a married woman, and by the pastor’s own philosophy, the issue should have been taken up with my husband, not my father.

They forget what St. Paul said (Galatians 3:28):

…All of you who were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

In the past I have felt that I ought not to publicly express an opinion that is different from my husband’s. I have even hesitated at times to admit to him privately that I could not agree with his position on one issue or another–and that is partly due to the fact that I naturally shrink from conflict, but also because of the environment in which I found myself. Is it any wonder? What were the messages I was hearing? Sermons are for the men. Women must receive Communion from men. Women are not permitted to listen to church meetings. If women vote in political elections, they should vote the way their husbands vote. They should believe what their husbands believe without question. Women should not be trusted to make decisions about the best way for them to give birth.² Anything that goes wrong in any area of life for the man, the woman, or the children, is the husband’s responsibility because he is the head of his family.³ And on and on it goes.

Some say this is patriarchy. It might be better to refer to it as hyperpatriarchalism, or patriocentricity, because there is a traditional Christian patriarchy and this is not it. And it’s no small thing. It is wrong, and it perverts the Gospel. It had an effect on me that was imperceptible to me at the time, but even as I questioned it, it was stunting my personal growth and distorting my own concept of myself. Looking at it now from a distance, I feel I’ve been freed from a kind of bondage. It was years later that I really began to see that, despite what I had thought, I did not escape completely; I could not get away from the guilt, the oppression, the bonds, the push to make me a non-person, to take from me my own thoughts and my own responsibilities…my personal relationship with my Lord and my God! I am moving farther and farther from this place in time and in thought, but the shedding is slow and gradual. I am relieved that it’s happening for me, and grieved for those who aren’t getting away.

—

¹Little ‘o’ orthodoxy, just so we’re clear.

²http://credenda.org/archive/issues/18-2childer.php

³Douglas Wilson, Federal Husband (Canon Press, 1999); pp. 25-26

When I began to see and acknowledge the abuses of my former church, and likewise the mistakes my parents made in my upbringing, one of the most common reactions I received was like this: “All parents make mistakes, so stop feeling sorry for yourself and make better choices if you think theirs were wrong.” I am bitter, they said, and I need to repent of this.

When I began to see and acknowledge the abuses of my former church, and likewise the mistakes my parents made in my upbringing, one of the most common reactions I received was like this: “All parents make mistakes, so stop feeling sorry for yourself and make better choices if you think theirs were wrong.” I am bitter, they said, and I need to repent of this.